Year in Review: The Main Wall

As K Art completed its first year around the sun on the 11th, we’d like to take this moment to reflect on one of our favorite spots in the space: The Main Wall. The official-unofficial gallery center has hosted several iconic artists and their work during our inaugural year. The Wall stretches nearly 40 feet across our first floor and allows a breath of fresh air. This breeze is unique as each installation has enriched the spirit of K Art and has granted our audience a walk with the artist. The Main Wall has become a staple in the gallery and a staple in our day-to-day work lives (always gloomier during days of transition). Working alongside it has provided a sense of comfort and empowerment that I cannot explain - an experience exclusive to the ground floor.

On December 11th, K Art officially opened its doors with More Than a Trace. Consisting of titans Duane Slick, Marie Watt, Lewis DeSoto, etc., the show challenged the current misrepresentation of Native Americans and First Peoples through themes of environmentalism, cultural identity, and connectedness. Despite their ancestral and artistic differences, all artists cohesively delivered a universal message - the desire to be more than a trace.

Multimedia artist Jeffrey Gibson is renowned for bridging American popular culture, western abstraction, and Indigenous symbolism. In this geometric series, once located on the Main Wall, Gibson fashions cultural hybridity in five distinct prints congruous to his fascination with abstraction. Originally fabricated digitally, the prints were screen-printed and collaged with additional screen-printed elements. They are now limited edition prints (which are no longer in production) held within vivacious frames, further speaking on their eclectic palette.

He appropriates and creates song lyrics, authored phrases, and personal mantras, and converts them into color-blocked text, enclosing them in angular patterns. This artistic hybridity emphasizes the visual language in his work, enriched by rainbow geometry, and arguably touches upon the aesthetics of computerized glitch art. Often, the western perspective views color and shape as purely formal. As Gibson explained in an interview for the exhibition, however, patterns of these elements are identifiable symbols about the artist in Indigenous culture.

In the spring of 2021, Brought to Light investigated different controversies within Native communities. Compared to any other group, Native American women in the United States are more than twice as likely to experience violence; 84% of Indigenous women have experienced violence in their lifetime. Highlighting these devastating statistics, four artists presented work addressing sexual assault, trauma, and loss of identity: Natalie Ball; Luzene Hill; Sonya Kelliher-Combs; and Julia Rose Sutherland.

The Main Wall hosted Sonya Kelliher-Combs’s A Million Tears installation from April to October, a physical response to the many painful accounts the artist has heard of abuse. Each canvas of the 52 is unique, presenting found items, synthetic flowers, and delicate handkerchiefs in acrylic and polymer coating. Some are 12" x 12", and some are 18" x 18"; their impact, however, still weighs the same. Many of Kelliher-Combs’s work combines organic and inorganic materials as a syncretic method of old and new techniques and traditions.

Speaking on these extreme cases of mistreatments in Alaska and Indigenous lands, the installation encompasses a sentimental longing for a past free from pain and trauma. Their call for innocence's return is engraved profoundly alongside bundles of Forget-Me-Nots and Dogwoods. These synthetic flowers reference visiting graveyards, especially in Alaskan Native communities. The handkerchiefs, restricted from movement, are stretched tightly across the canvas, almost reminiscent of stressed skin, especially in the installation’s warmer tones.

In late September, we announced our third exhibition: Ga’nigöi:yoh: G. Peter Jemison. In celebration of our represented artist, a six-decade retrospective surveying paintings, parasols, and, most notably, his paper bags took home in our space. Translating to "The Good Mind," the show explores the Seneca man's life through triumphs and tribulations and discovers how good and evil will naturally balance one another. Ga’nigöi:yoh is currently on view until January 7th, 2022.

The Main Wall presents a tetralogy of acrylic on canvas pieces to commemorate the unification of organic content, color block, and indigenous identity. With no intentions of becoming a cohesive series, the works, created consecutively during the early 1970s, exemplify ideas of modernism and "green abstraction." Jemison is a fearless experimentalist in his practice, approaching obscure objects as viable media. The 1970s, however, experienced a shift in his content due to political and social events occurring in the same timeline.

Cantaloupe, 1974, invites us to a seat at the table with a fruitful communion of melon slices. Listening to the Watergate hearings, he creates a DNA-like structure within the fruit, perhaps to comment on its once wholeness. Onëö (Oneho), 1972, or White Corn, is a compilation dedicated to the fall season: ripe corn ready to harvest; crimson leaves casting cobalt shadows; tree logs cut in preparation for fire; icy blue rocks foreshadowing the months ahead. 2 Blue Lakes, 1971, is Jemison's first endeavor in incorporating naturalistic imagery in his paintings. During its creation, he rubbed its freshly-painted surface on the grass to apply different layers of texture. Finally, Red Power, 1973, reflects the American government's perspective on the American Indian due to the Occupation of Wounded Knee with a monochromatic and prideful sand burr, a small flower maximized and empowered with sharp spikes. These early years in the 70s also saw a rise in Iroquois nationalism, causing Jemison to think critically of his own Seneca identity. Due to a storage fire in ’74, these works are the last of their kind.

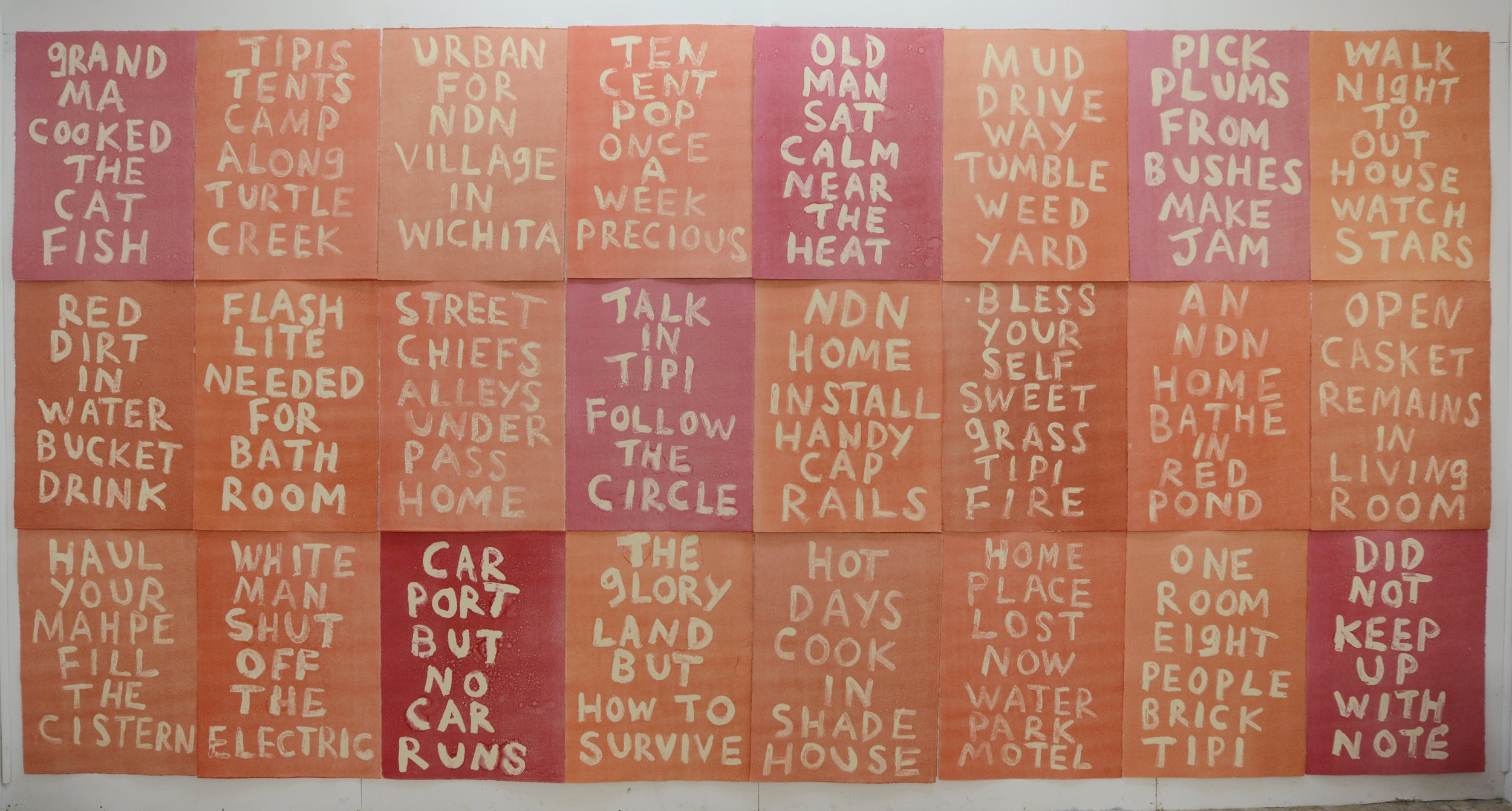

Heap of Birds, An NDN Home (primary and ghost monoprints), Ink on Rag Paper, 2018

Heap of Bird's monoprint series An NDN Home will take over the gallery's Main Wall for a limited time beginning January 21, 2022. Forty-eight prints total, the installation contains 24 unique primary prints and 24 ghost prints. With his primary prints, Heap of Birds presents the actual reality of Native life - a direct visual and creative procedure. On the other hand, the ghost prints are not as pristine as their counterpart; they represent America's misunderstanding of the Indigenous, a faint awareness plus a downgraded worth of Native people. Both will be presented alongside one another, stretching over 30 feet wide and 7 feet tall.